The poet Robert Bloomfield, author of The farmer’s boy, was born in Suffolk two hundred and fifty years ago, in December 1766. Of humble parentage, he worked briefly as a labourer on a nearby farm before moving to London to take up the trade of cobbler. The success of The farmer’s boy, a poem of some 1,500 lines describing the countryside and agricultural life through the seasons of the year, brought Bloomfield an intense though temporary celebrity, and a lasting reputation as one of the most significant of the uneducated rustic poets of the English tradition. John Clare, nowadays by far the more famous of the two, called Bloomfield ‘the first of Rural Bards’.

To mark the anniversary of his birth, a new exhibition in the Cambridge University Library’s Entrance Hall celebrates Bloomfield’s achievements as represented by his own writings and by works of art and music inspired by them. It draws on the Library’s Special Collections, including manuscript verse and autograph correspondence, and benefits from the acquisition in 1984 of the Bloomfield collection assembled by Robert F. Ashby (exhibits with CCA–CCE.34 classmarks).

The exhibition opens with an apparently unpublished manuscript memoir of Bloomfield, written by Walter Bloomfield, the son of the poet’s last surviving nephew; in an introductory letter the author declares that ‘the major portion of it contains information which must be new to everybody unconnected with my family’. The text is prefaced by a pedigree showing, among other things, Robert Bloomfield’s relationship to Charles James Blomfield (1786–1857), bishop of London.

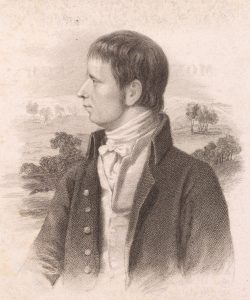

Bloomfield worked on his masterpiece, The farmer’s boy, between May 1796 and April 1798. He composed most of the poem at his cobbler’s bench, keeping long sections in his head before they were written down: he chose rhyme because he found it easier to memorise than blank verse. The poem was championed by the Suffolk squire and radical editor Capel Lofft, and through his influence it was published in 1800. A copy of the first edition is on display. Following the success of The farmer’s boy many engraved portraits of Bloomfield appeared, often serving as frontispieces to editions of his works; the example in the exhibition, and shown above, engraved by Thomas Woolnoth (1785–1857) after Thomas Charles Wageman (1787–1863), appeared in the Ladies’ monthly museum and is unusual in setting Bloomfield against the backdrop of a rustic landscape.

Several settings of Bloomfield’s verse to music are known, most of them dating from his lifetime or shortly afterwards. The exhibition includes a setting of ‘Rosy Hannah’ by his elder brother Isaac (1762–1811), printed on paper watermarked 1801, which may have appeared before the poem was included in Bloomfield’s second collection, Rural tales, ballads, and songs, in 1802.

One of Bloomfield’s most popular poems, ‘The Fakenham ghost’, a humorous ballad ‘founded on a fact’ telling the story of an elderly woman who, walking home at night and fearing pursuit by supernatural terrors, discovers that she has been followed to her door by an ass’s foal, is represented in both manuscript and print. The manuscript appears to be a fair copy in the poet’s own hand; it is much more lightly punctuated than the published versions, and differs from them in some wordings. First collected in Rural tales, the poem was afterwards reprinted separately both in illustrated editions and in musical settings, and a broadsheet which is the earliest recorded illustrated version is on display. The unsigned plate follows the poem closely in details such as the hillside copse, the grazing deer, and the park gate, but makes no attempt to render the nocturnal setting.

Although associated through his poetry with Suffolk, Bloomfield spent little of his adult life there, and in his later years, which were marked by illness and financial difficulties, he lived in the small Bedfordshire town of Shefford. A handwritten letter on show, sent from Shefford to a Mr May less than a year before Bloomfield’s death, appears to refer to a possible reprinting of Nature’s music, his 1808 prose treatise on the Aeolian harp.

There are also posthumous publications on display, charting Bloomfield’s continuing appeal to later generations. Illustrated editions of Bloomfield’s verse appeared throughout the nineteenth century, and the 1857 first printing of the Routledge ‘complete’ edition of his works with engravings by Myles Birket Foster (1825–1899), which was reissued at least five times over the following thirty years, can be seen. A colourful edition of The horkey: a ballad, with illustrations by George Cruikshank, was published by Macmillan and Co. in 1882; ‘Horkey’ was a term for the harvest home feast current in the East of England. Bloomfield’s poem, subtitled ‘a provincial ballad’ when first printed in 1806, describes customs particularly associated with Suffolk harvest festivities, and which he believed were ‘going fast out of use’, and incorporates a number of East Anglian dialect terms. The exhibition finishes with a diminutive pamphlet edition of Bloomfield’s The drunken father, published around 1880 in aid of the temperance movement, with a preface by Walter Bloomfield, the poet’s kinsman and author of the manuscript memoir which opens the exhibition.

‘“The first of rural bards”: Robert Bloomfield (1766–1823) in word, music and image’ runs at Cambridge University Library until Saturday 14 January 2017 (closed Sundays and 24 December–2 January inclusive) during normal Library opening hours. For further information contact John Wells (e-mail: jdw1000[at]cam.ac.uk, telephone: 01223 333055).