Cambridge University Library has recently been using a generous grant from the Howard and Abby Milstein Foundation to augment its provision of online exhibitions. The re-designed Exhibitions homepage has links to the resources in the new format, which have been created using a customised platform based on WordPress. Two recent virtual exhibitions in particular may be of interest to those involved with modern literary manuscripts.

Flesh wounds: David Holbrook and D-Day concerns David Holbrook, later well-known as a writer, educationist and controversialist, who landed in Normandy as a twenty-one year old tank commander on D-Day, 6 June 1944, and recounted his experiences in his autobiographical 1966 novel Flesh wounds, which has been described as ‘one of the few war novels that is conceived on the same plane as Wilfred Owen’s war poems’. The exhibition marks the 70th anniversary of the Allied invasion of Europe and draws on Holbrook’s literary archive, donated to the Library by his family in 2012.

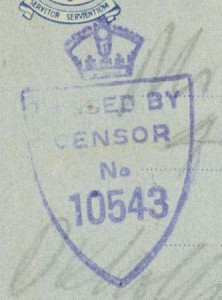

Holbrook served in the East Riding Yeomanry, an armoured regiment which operated American-designed Sherman tanks on D-Day. The exhibition includes a letter, written on a NAAFI (Navy Army & Air Force Institutes) letter form, sent by Holbrook from the Normandy beachhead to his parents in Norwich, in which he describes the Nazis as ‘brutal overgrown boyscouts’, and says the Germans ‘fight cleverly & dirtily – chiefly in the evenings.’ An amended version of the letter was printed in Flesh wounds.

Another letter on show was written in Leeds during Holbrook’s convalescence from an infected wound sustained during the shelling of his unit’s headquarters on 21 June, and shows an early formulation in prose of experiences that were later to form the basis of episodes in Flesh wounds. The display also includes sheets from an autograph draft of the ‘D+2’ chapter of the novel, recounting events in Normandy on 8 June 1944; this contains a lengthy (and highly uncomplimentary) account of the British Sten gun, and a comparison of it with its German equivalents and with weapons of earlier eras, which was largely discarded in the published version of the novel. Copies of some of the many printings of Flesh wounds, in hardback and paperback, are also included.

Holbrook returned to the sites of the Normandy battlefields in 1994 for the fiftieth anniversary of the campaign, and provided an account of his visit for members of his old regiment: a typescript of this short text concludes the exhibition, and gives an account of the wording on the gravestones of former comrades killed by the shelling in which Holbrook was himself wounded: ‘On the grave of Major Tony Fitzwilliam-Hyde [sic] it says, “The people that do know their God shall be strong and do exploits”. On that of Sergeant L Harness, “Whosoever reads his name salutes a mighty company who died that we might be free”. On the grave of Cpl. A. Emsley, “Proud and treasured memories of a darling husband and daddy. Age 23.”’

‘rhythm and line and necessity’: John Riley and Czargrad traces the composition of Riley’s poem Czargrad, a seminal work in the alternative tradition of British poetry exemplified by the so-called ‘Cambridge School’ in the 1960s and 1970s. Riley was born in Leeds in 1937 and was educated at Pembroke College, Cambridge, between 1958 and 1961. He took employment as a schoolteacher before leaving the profession to concentrate on literary work. He was killed in a street robbery in Leeds in 1978, aged 41. John Riley’s literary papers were donated to Cambridge University Library by his wife, Carol Riley Brown, in 2013.

Czargrad holds a central place in Riley’s work. Writing in PN review in 1981, Douglas Oliver called it Riley’s ‘broadest, most comprehensive poem’, evoking ‘an imagined, pristine, Eastern Orthodox city, shining a little with Byzantine gold, ambiguously holding out promise of true government, of true citizenship, and held in mind-sight by tremulous energies of artistic creativity.’ The poem, written in four parts in the years preceding Riley’s reception into the Russian Orthodox Church in 1977, uses incantatory language to interweave English and Eastern scenes with recurrent imagery of wings, water, flowers, leaves, domes and light.

The exhibition puts on display notebooks and worksheets containing a selection of Riley’s manuscript and typescript drafts of the poem, together with printed items and correspondence relating to the work. It draws both on the John Riley Papers, MS Add. 10038; Riley’s letters to his friend Michael Grant in MS Add. 10000; and the Library’s printed book collections.