Extended until the 2nd October, there is still time to visit The Worlds of Mervyn Peake, a free exhibition in the British Library Folio Gallery.

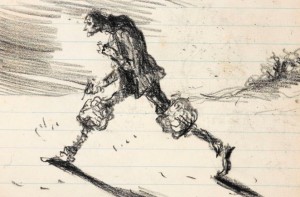

The exhibition showcases the Peake Archive which was acquired by the Library last year with generous support from the Art Fund, the Friends of the British Library, the Friends of the National Libraries and individual donors. Highlights include Peake’s notebooks, which are full of working drawings of his characters, sketched to help him imagine the kinds of things these peculiar people might say. Also on view are his original drawings for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, rivalling Tenniel’s illustrations in their eccentricity and fearsomeness as well as the virtuosity of Peake’s cross-hatching technique.

The exhibition presents a thorough picture of Peake the polymath: as novelist, poet (of both serious and nonsense verse), painter, illustrator and playwright. His work is seen through the prism of the worlds he inhabited, both imaginary and real – from his birth in China, to Sark, London and his trip to Germany as a war correspondent in 1945 – these places all made a lasting impression on the settings and subject matter of his creative output.

Peake’s papers and drawings sit alongside correspondence from the archive. There is Graham Greene’s letter about Titus Groan which takes Peake to task for ‘spoiling a first-class book by laziness’. C S Lewis’ letter on Gormenghast praises Peake for making him ‘experience what he never experiened before… a new Universal’. And then there’s a note from Dylan Thomas, the Peakes’ friend and neighbour who often turned up on their doorstep somewhat the worse for wear; this note asks Mervyn for the loan of a coat and trousers (apparently just two of the garments which Thomas borrowed from Peake over the years; none were ever returned).

A deeply sympathetic man, a keen observer and a practical joker, this exhibition offers the chance to trace all these facets of Peake’s character in the writings and drawings he left behind.