Dawson Turner, the banker, antiquary, and leading light of autograph collectors in the early nineteenth century, claimed that he had ‘never met with the man who was not gratified to see how Newton wrote, or how Milton and Bacon formed their letters’. Since poetry is the most intense and heightened mode of language, fascination with the physicality of an autograph text, and the excitement provided by a sense of proximity to the writer, has often been especially strong in the case of poetical manuscripts.

The emergence of respect for autograph writings, which does not seem to have been common before the eighteenth century, has been attributed to the proliferation of print culture and the uniformity of mass-produced books. Walter Benjamin defined a work of art’s ‘aura’ as ‘its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be’, and the American poet Dana Gioia, quoting Benjamin, extended this idea to literary manuscripts in order to explain the special value accorded to autograph texts. Yet Gioia’s essay has appeared in The Hand of the Poet (New York, 1997), a machine-made volume of printed facsimile reproductions of poets’ handwriting, and in actual practice the medium of print has proved to be a means by which some measure of the aura of autographs can be communicated.

Showing Their Hands: Poets’ Autographs in Facsimile, a new exhibition in Cambridge University Library (see foot of post for access information), traces some of the ways in which poets’ handwriting has been disseminated in print. The term ‘autographs’ is used in the sense of any writing in the poets’ own hands, not merely signatures, and the exhibition includes images of poems, letters and legal documents by poets as diverse as Torquato Tasso, George Herbert, John Keats, Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Edna St. Vincent Millay and Federico García Lorca. Volumes with facsimile autographs represent a distinctive sub-genre of the illustrated book, and in the same way as the autographs which gave rise to them, these publications have become a field for collectors and students in their own right.

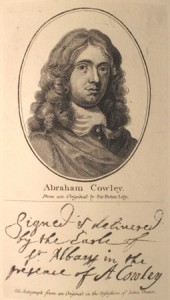

The practice of engraving examples of handwriting pre-dated the concern for specifically autographic material, and reproductions of medieval hands were produced in the first half of the eighteenth century for the benefit of antiquarian scholarship. Some early collections of autograph facsimiles were similarly intended as aids to historians and librarians, by helping them to identify the writers of original documents. Early facsimiles were a branch of the engraver’s art, and there were strong links between their production and the wider print trade; it was not uncommon for facsimiles of signatures or other scraps of autograph writing to be combined with portraits, since each was considered, in Dawson Turner’s words, to be an ‘indispensable accompaniment to biography … and both for the same cause, as clues to the deciphering of character’.

By the early Victorian period autograph collecting had become an established pastime among the middle classes, bringing about a range of publications aimed at a popular audience. The exhibition includes examples of these, including the Historical and Literary Curiosities of 1840, a gallimaufry of pictorial representations frequently combining architectural or topographical imagery with related facsimiles, and The Autographic Mirror (1864–6), a periodical which reproduced documents in the hands of a wide range of contemporary and historical figures—‘Sovereigns, Statesmen, Warriors, Divines, Historians, Lawyers, Literary, Scientific, Artistic, and Theatrical Celebrities’—from Britain and overseas. Early compilations of facsimiles tended to give pride of place to royalty, nobility and political figures, but in the twentieth century volumes were produced devoted to autographs of literary, and specifically poetical, authors.

The value of manuscript materials for deepening an understanding of poetical composition has long been understood, as has the usefulness of facsimiles in disseminating examples of the process. The exhibition includes the second volume of Isaac D’Israeli’s Curiosities of Literature (1793), with a plate showing a page of the draft of Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad. In his accompanying text, D’Israeli provided an early summary of the interest in studying a writer’s working papers: ‘The lover of poetry will not be a little gratified, when he contemplates the variety of epithets, the imperfect idea, the gradual embellishment, and the critical rasures which are discoverable in this Fac Simile. The action of Hector, in lifting his infant in his arms, occasioned Pope much trouble….’

In the last third of the twentieth century there were several attempts to produce facsimile editions of extensive—even comprehensive—collections of individual poets’ surviving manuscripts. Byron, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson, Whitman and Yeats have all had entire series of volumes dedicated to reproductions of their autograph poetry. At the same time, however, the poetical facsimile has been a field for more individualized publications, drawing on the traditions of fine press printing in matters such as layout, paper, edition size, and the typography of the accompanying letterpress; the ink and paper of a facsimile can be greatly superior to those of the original documents. Most facsimiles are issued in bindings bearing no relationship to the original item, but occasionally an attempt is made to recreate the physical characteristics of the source document more closely, and as an example the exhibition features a reproduction of the 1888 article said to have caused the breach between Algernon Charles Swinburne and James McNeill Whistler, published in the form of 13 loose leaves on blue paper.

A wide range of methods of producing facsimiles is demonstrated by the exhibition, from steel engravings and lithography through to colour photography. Advances in digital technology have opened up new avenues for the reproduction of poetical autographs, and facsimiles made available online or by app are represented. The exhibition begins and ends with facsimiles of Shakespeare’s signatures on his will. The first is in the form of an eighteenth-century engraving, the second a twenty-first century full-colour photographic reproduction issued as part of a multi-media publication. In spite of the disparity in imaging technologies, the deterioration in the condition of the original document in the 228-year interval between the production of the facsimiles has meant that the earlier version retains evidential value in relation to Shakespeare’s handwriting.

Showing Their Hands: Poets’ Autographs in Facsimile runs in the North Front Corridor at Cambridge University Library from Monday 17 September to Saturday 1 December, during normal Library opening hours. Library readers who are members of the University are welcome to bring up to two visitors at a time to see exhibitions. Members of the public who do not hold Library readers’ tickets may be able to make an appointment with the curator to gain access to the exhibition area. For further information contact John Wells (e-mail: jdw1000@cam.ac.uk, telephone: 01223 333055).